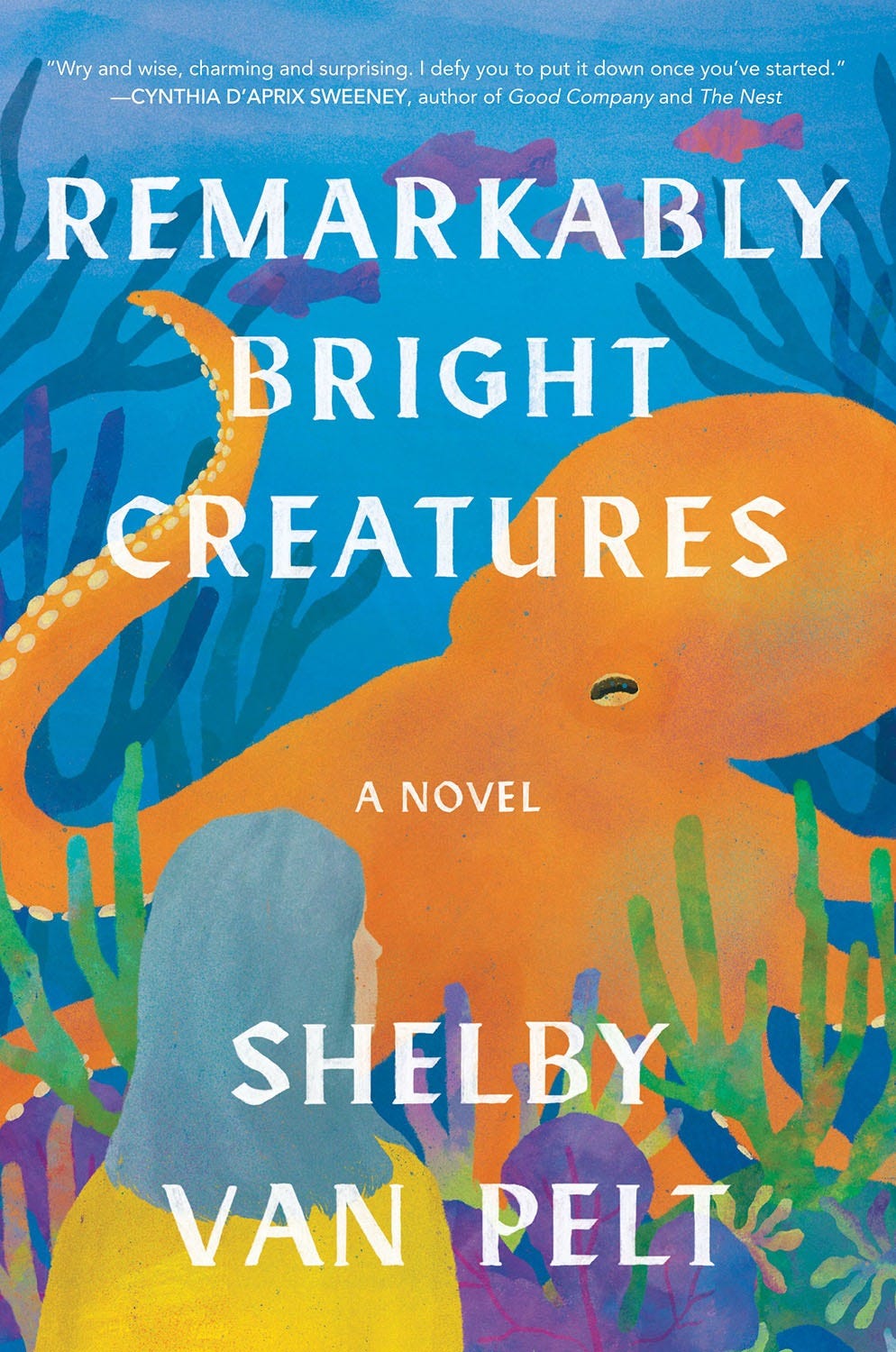

Remarkably Bright Creatures

Shelby Van Pelt

Fiction, Absurdist

Audiobook finished January 4, 2024

Review

Prepare to identify as an octopus, because this book shows the humanity of intelligent creatures through the connections our species forge with them. This debut novel from a woman raised in the Pacific Northwest did not disappoint. It was witty, kindred, funny, and sensitive. It was an easy and exciting read that kept me engaged through one of the most difficult senses to jockey: the heart.

Our protagonist should be Tova, the widow who lost her son and husband and uses her job at the aquarium to deal (or avoid) her grief. Despite the focus on Tova throughout the book, this book is not about her at all.

The cover features a bright orange Marcellus (the octopus,) and so does the aquarium, the book, and our attention. The titular phrase is used not to describe the world’s most intelligent invertebrate, but instead, his captor.

“Humans. For the most part, you are dull and blundering. But occasionally, you can be remarkably bright creatures.”

Marcellus knows he has a longer lifespan than most octopuses, averaging three to five years, and that his time is running out. His species can recognize visitors, solve puzzles, and raise hell for any humans who attempt to contain them. These incredibly smart animals (to rephrase the book’s title) can open child-proof packaging and use human tools, even valves and equipment that many humans could not. This makes the giant Pacific octopus a particularly good candidate for animal personification in a book, and I applaud the author for the idea.

“Marcellus was, in fact, an exceptional octopus.”

The widow Tova is a lovable and relatable character, in fact, even the bit players in the story are rendered with care. Van Pelt sketches a diary of controlled madness in the aquarium staff and guests which we enjoy through the eyes of a creature who has every reason to hate us and still finds a way to love.

“It seems to be a hallmark of the human species: abysmal communication skills. Not that any other species are much better, mind you, but even a herring can tell which way the school it belongs to is turning and follow accordingly. Why can humans not use their millions of words to simply tell one another what they desire?”

It would be easy to write this story off as literary fiction, a tale of a widow and an animal forming a bond, and it would still be quite pleasing to read for its lovable tone and messaging about grief, loss, and imprisonment. But, at the end of the day, Remarkably Bright Creatures is a mystery. Tova’s son was lost many years ago, and the octopus knows more than he is able to communicate. Despite feeling the mystery’s solution approaching, it seemed to sneak up behind me as though I were watching for it through the windshield and it appeared in my rear-view mirror.

“Day 1,361 of My Captiv- Oh, Let Us Cut the Shit, Shall We? We Have a Ring to Retrieve.”

I picked up this book because I’ve been deeply interested in the absurdist sub-genre and really enjoyed some weird books last year (I’d put The Factory at the top of that list.) While Remarkably Bright Creatures is truly absurd, it’s not entirely outside the realm of possibility so I’d recommend it to anyone who wants to dip their toe into the strange without having to suspend their disbelief entirely.

“Humans are the only species who subvert truth for their own entertainment.”

The book has some dark themes, but treats them with reverence and respect while staying fun and quirky. Full of deep meaning which bubbles to the surface through the thoughts of its characters, this book is full of quotable moments.

On grief:

“Her void held no sweetness, only bitterness; at the time, Erik had been gone five years. How delicate those wounds were back then, how little it took to nudge the scabs out of place and start the bleeding anew.”

On the triviality of trends:

“But young women don’t want bone china anymore. They’ve no use for old Swedish things. They have their own dinnerware, probably from Ikea. New Swedish things.”

On the importance of community:’

“As one would gather from the name, the Knit-Wits began as a knitting club. Twenty-five years ago, a handful of Sowell Bay women met to swap yarn. Eventually, it became a refuge for them to escape empty homes, bittersweet voids left by children grown and moved on.”

On being sensitive in captivity:

“When I choose to hear, I hear everything. I can tell when the tide is turning to ebb, outside the prison walls, based on the tone of the water crashing against the rocks. When I choose to see, my vision is precise. I can tell which particular human has touched the glass of my tank by the fingerprints left behind.”

On trying to help others:

“And, well . . . you can’t fix someone who is determined to stay broken.”

On life:

“The deal is never anyone's fault. But you control the way you play.”

On living: